"Southside" Compared to Raymond Chandler in Los Angeles Review of Books

/LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS , January, 2015.

Tyler Dilts on Southside by Michael Krikorian

Chandler’s Shadow

“WE’RE GOING TO TALK about Raymond Chandler for the next four hours,” the tour guide says. I’m on a bus with about 30 people on “Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles: In A Lonely Place, An Esotouric Bus Adventure.” The driver has just pulled to the curb on Olive Street in front of the Los Angeles Athletic Club and across the street from Giannini Place, where Chandler worked as VP of the Dabney Oil Syndicate until booze, flakiness, and dalliances with female employees led to his dismissal and then to his writing career.

We get off the bus and cross the street to visit the Art Deco entrance to the Oviatt Building. The tour guide recites the history of the building and reads a passage from Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake that describes where we’re standing: “The sidewalk in front of the building had been built of black and white rubber blocks.” The rubber was removed to be recycled for the war effort, but other things have remained the same; he continues: “They were taking them up now to give to the government, and a hatless pale man with a face like a building superintendent was watching the work and looking as if it was breaking his heart.” Much of the architectural detail survived the decades — sconces and stained glass and Art Deco detailing — and much of today’s Los Angeles was Chandler’s setting 70 years ago. Anyone writing crime fiction set in Southern California today is writing in Chandler’s milieu.

Raymond Chandler, the author of The Big Sleep and The Long Goodbye, is widely regarded as a titan of the subgenre of crime fiction. Among writers and scholars, though, his essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” first published in The Atlantic in 1944, is nearly as well known as his fiction. In this takedown of the English tradition of mystery stories, he lambasts the Golden Age of detective fiction (“Sherlock Holmes after all is mostly an attitude and a few unforgettable lines of dialogue”) and, after offering a detailed critique of a number of those stories, offers this summation: “There is a very simple statement to be made about all of these stories: they do not come off intellectually as problems, and they do not come off artistically as fiction.”

Later in the essay, Chandler cites Dashiell Hammett as representative of a different style of detective fiction, one that deals in realistic situations and uses realistic violence to achieve its ends. Due to this realism, Chandler argues, this fiction has the potential to engage in a kind of literary art that is otherwise absent in the genre. Of those who challenged Hammett’s work as mysteries, he says, “These are the flustered old ladies ... [who] do not care to be reminded that murder is an act of infinite cruelty.”

In the first few paragraphs of his essay, Chandler describes the ideal detective. In a well-known passage of the work, he writes: “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.” This distils the essence of Philip Marlowe, the intrepid knight-errant protagonist of Chandler’s seven novels and most of his short stories. He wasn’t the first detective of his kind — but he was perhaps the finest — and has become archetype of hard-boiled protagonists in the decades since his creation.

What sets Chandler and others of the hard-boiled school apart from the broader genre of mystery fiction is the idea that violence has consequences from which one can never fully recover. Even if the murder is solved and the killer brought to justice, order can never be completely restored, because it never truly existed in the first place. With his fiction and (even more prescriptively) with “The Simple Art of Murder,” Chandler established a paradigm for literary crime fiction that would dominate the genre for well over half a century.

Due to the many reproductions of his novels, that paradigm has necessarily included Chandler’s literary style, as well as his vivid depictions of Southern California, and both aspects have become conventions of the hard-boiled style. Two recent novels — Matt Coyle’s Yesterday’s Echo and Michael Krikorian’s Southside — highlight these sometimes disparate aspects of the genre.

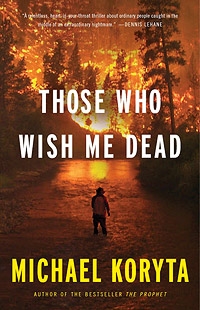

Michael Krikorian’s Southside grapples with this issue in a manner from which most Southern California crime fiction shies away. Krikorian is a former gang reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and his considerable authority on the subject is clear. The novel’s protagonist, Michael Lyons, covers gangs for the city’s major newspaper, and when he’s shot outside his favorite bar after a midday double, a complex plot of revenge and retribution begins to unfold.

Krikorian nails the newspaper culture with both humor and venom. Almost as soon as the shooting occurs, Lyons’s colleagues form a “Who shot Mike?” betting pool. The speculation grows even more intense when a tape recording of a conversation between Lyons and a gang shot caller named King Funeral, in which he suggests being shot might give him more street cred, is made public. As the story develops, we see both the newspaper business and the criminal investigation in vividly realistic detail.

We know early on, though, that Lyons was not responsible for his own attack. No. The shooter was Eddie Sims. There’s no mystery in this — Krikorian reveals the attacker’s identity early on. We know not only who did it, but we also see more of what Sims has in store. Years earlier, his son, who had avoided the gangs so many of his peers were involved with, was killed in an incident involving the leader of a local crew, Big Evil. After Sims sees a documentary that shows Big Evil flourishing as a trustee in a super-max prison, he decides to take revenge on those who failed to seek the death penalty in Big Evil’s trial. Death Row, Sims believes, even without the ultimate punishment, would still be a fitting fate for Big Evil. Lyons is Sims’s first target because the reporter wrote a profile of the gang leader that humanized him and granted him even more notoriety than he already possessed.

Krikorian does much the same thing for his characters here as Lyons does for those he profiles. He gives voice to the realities of their lives in South Central Los Angeles in a way Chandler never could. Eddie Sims, in all his grief and loss and capacity for senseless violence, is the most compelling of the central characters. When Sims is on the run and holed up in a cheap motel, Krikorian writes that “he stayed in his room and watched the news. There was nothing of interest. He finally fell asleep around three in the neon morning, his reloaded S&W revolver in the nightstand drawer atop the Gideon Bible.” Even as we’re horrified we feel empathy; Sims is recognizably and understandably human. He’s a character who, in Chandler’s world, would be invisible, but whom Krikorian makes visible.

Southside is written in a combined first- and third-person perspective, but the portions written in the third person achieve an authenticity and authority that is absent in Lyons’s first-person point of view. Reading, I had the impression that Krikorian was trying too hard to fit Lyons into the mold of the hard-boiled hero Chandler described in “The Simple Art of Murder,” and wondered if Lyons, as he goes down the meanest streets Los Angeles has to offer, might in fact be mean himself. By the end, tarnished though he is, Lyons is shown not to be mean, but for a novel that examines the underside of Southern California (untouched since before Chandler began writing), that is only a minor consideration. While Lyons’s redemptive actions in the novel’s final act might not ring entirely true, ultimately, Krikorian’s authority on the subject overcomes the limitations of his protagonist’s characterization, and Southside becomes an examination of a Los Angeles too seldom seen in serious crime fiction.

Krikorian's Southside and Coyle's Yesterday’s Echo can be read as two distinct aspects of Chandler’s legacy. In terms of style, voice, and tone, Matt Coyle ably follows in the master’s stylistic footsteps and evokes the literary quality with which Chandler imbued the Southern Californian tradition of detective literature.

Krikorian, on the other hand, builds an authentic Southern California landscape that allows the vast blind spots in Chandler’s vision to be at least partially filled in. Perhaps, it’s fitting that Krikorian’s rendering of this landscape is more problematic and less cohesive than Coyle’s. Chandler’s creation of the mythic Philip Marlowe was so successful it turned the author himself into a figure almost as mythic. These two novels find the value not only of furthering the myth, but also of tearing it down.

¤

The bus tour ends a block away from where it began, in the rapidly gentrifying Los Angeles Arts District. The tour guide regales us with the last sad anecdotes of Chandler’s later years and his suicide attempt; I’m struck by how thoroughly and effectively the tour has deconstructed Chandler the writer and replaced him with Chandler the man. Gone is the myth, and present is the humanity, faults and failings in full relief.

Chandler argues midway through “The Simple Art of Murder” that all fiction, from the most populist to the most literary, is about escapism. It’s not hard to imagine the writer’s greatest creation, Philip Marlowe himself, as an idealized, wish-fulfilling fantasy. Marlowe may have been neither tarnished nor afraid, but it’s become impossible for me to think of Chandler as anything but the embodiment of those two qualities, and surprisingly, I like him even more for it

Ed Boyer, my former editor at the Los Angeles Times, deep into "Southside" at a local pizzeria.

.

.